Structured Procrastination on Cities, Transport Policy, Spatial Analysis, Demography, R

Saturday, December 28, 2019

Thursday, December 26, 2019

Building up or spreading out? Urban growth across 478 cities

New paper by the Seto Lab in collaboration with Anjali Mahendra (who is also onTwitter).

Mahtta, R., Mahendra, A., & Seto, K. C. (2019). Building up or spreading out? Typologies of urban growth across 478 cities of 1 million+. Environmental Research Letters, 14(12), 124077.

Abstract

ps. The image below was taken from the WRI report that originated the paper.

Mahtta, R., Mahendra, A., & Seto, K. C. (2019). Building up or spreading out? Typologies of urban growth across 478 cities of 1 million+. Environmental Research Letters, 14(12), 124077.

Abstract

Urban form in both two- (2D) and three-dimensions (3D) has significant impacts on local and global environments. Here we developed the largest global dataset characterizing 2D and 3D urban growth for 478 cities with populations of one million or larger. Using remote sensing data from the SeaWinds scatterometer for 2001 and 2009, and the Global Human Settlement Layer for 2000 and 2014, we applied a cluster analysis and found five urban growth typologies: stabilized, outward, mature upward, budding outward, upward and outward. Budding outward is the dominant typology worldwide, per the largest total area. Cities characterized by upward and outward growth are few in number and concentrated primarily in China and South Korea, where there has been a large increase in high-rises during the study period. With the exception of East Asia, cities within a geographic region exhibit remarkably similar patterns of urban growth. Our results show that every city exhibits multiple urban growth typologies concurrently. Thus, while it is possible to describe a city by its dominant urban growth typology, a more accurate and comprehensive characterization would include some combination of the five typologies. The implications of the results for urban sustainability are multi-fold. First, the results suggest that there is considerable opportunity to shape future patterns of urbanization, given that most of the new urban growth is nascent and low magnitude outward expansion. Second, the clear geographic patterns and wide variations in the physical form of urban growth, within country and city, suggest that markets, national and subnational policies, including the absence of, can shape how cities grow. Third, the presence of different typologies within each city suggests the need for differentiated strategies for different parts of a single city. Finally, the new urban forms revealed in this analysis provide a first glimpse into the carbon lock-in of recently constructed energy-demanding infrastructure of urban settlements.

ps. The image below was taken from the WRI report that originated the paper.

Marcadores:

Morphology,

Urban Sprawl

Tuesday, December 24, 2019

Friday, December 13, 2019

The mobility patterns of historically notable individuals

A new study using Natural Language Processing techniques to retrieve historical information from Wikipedia and analyze the spatial mobility patterns of historically notable individuals. A nice and inventive method to study historical mobility patterns. Science can be incredible and fun. (HT Marco De Nadai)

Lucchini, L., Tonelli, S. & Lepri, B. Following the footsteps of giants: modeling the mobility of historically notable individuals using Wikipedia. EPJ Data Sci. 8, 36 (2019) doi:10.1140/epjds/s13688-019-0215-7

image credit: Lucchini et al 2019

Marcadores:

Computational social science,

History

Thursday, December 5, 2019

How much time do we spend with other people as we grow old?

A couple of years ago, I posted this chart showing how much time we spend with other people as we grow old. The chart was created by Henrik Lindberg using data from the America Time Use Survey, and the code to recreate this chart in R is available here.

p.s It's my birthday today and birthdays are always a good moment to reflect about life :)

Marcadores:

Biographical note,

Life Cycle

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

geobr v1.1 is on CRAN

The geobr package in R is probably the easiest and fastest way to download shapefiles and official spatial data sets of Brazil. The package includes a wide range of geospatial data available at various geographic scales and for various years with harmonized attributes, projection and topology.

You can find a simple tutorial on how to use the package here.

You can find a simple tutorial on how to use the package here.

The new release of geobr v1.1 includes 19 data sets:

- country

- region

- state

- meso region

- micro region

- intermediate region

- immediate region

- municipality

- weighting area

- census tract

- statistical grid

- urban areas

- health facilities

- indigenous land

- conservation units

- biomes

- legal Amazon

- semiarid

- disaster risk areas

Friday, November 29, 2019

Awarded research on historical inequality in Brazil

I am very proud to share that my friend and colleague at Ipea Pedro Souza has been awarded the Prêmio Jabuti for his book 'A History of Inequality: the concentration of top incomes in Brazil between 1926-2013'. The Prêmio Jabuti (the "Tortoise Prize") is the most prestigious literary award in the country. The book is based on his PhD thesis, which has already received two national awards btw.

If you read Portuguese, you can buy Pedro's book here, or download his PhD thesis here. There is a paper in English summarizing some of the key findings of his research. I've also posted the English abstract of his thesis below.

Souza, Pedro H. G. F. de. “A desigualdade vista do topo : a concentração de renda entre os ricos no Brasil, 1926-2013”, 12 de setembro de 2016. https://repositorio.unb.br/handle/10482/22005.

This dissertation uses income tax tabulations to estimate top income shares over the long-run for Brazil. Between 1926 and 2013, the concentration of income at the top of the distribution combined stability and change, diverging from the European and American patterns in the 20th century. Contrary to benign industrialization and modernization theories, there was no overarching, long-term trend. Most of the time the income share of the top 1% of the adult population fluctuated within a 20%--25% range, even in recent years. Still, top income shares had temporary yet significant ups and downs which largely coincided with the country's most important political cycles. The top 1% income share increased during the Estado Novo and World War II, then declined in the early post-war years and even more so in the second half of the 1950s. The 1964 coup d'état reversed that trend and income inequality rose back to post-war levels after a few years of military rule. The 1970s were marked by instability, but top income shares surged again in the 1980s. The share of the 1% then decreased somewhat in the 1990s and perhaps the mid-2000s. There were no real changes since then. In addition, this dissertation analyzes the concentration of income among the rich, provides international comparisons of top income shares, and contrasts the income tax series with estimates from household surveys. The income tax series are also used to compute “corrected” Gini coefficients which take into account the underestimation of top incomes in household surveys. The major research questions are comparative and historically oriented, and I argue in favor of an institutional interpretation of the results. The motivation for and implications of this approach are presented in the more theoretical chapters that precede the empirical analysis. In these chapters, I engage with the history of ideas about inequality and social stratification and highlight the long and heterogeneous tradition of studies about the rich and the wealthy. My main argument is that the academic and political concern with distributional issues flourishes when inequality is conceived in binary or dichotomous terms.

Marcadores:

Brazil,

History,

Inequality,

Ipea,

Prata da Casa

Wednesday, November 27, 2019

An open-source framework for segregation measures

New paper by Renan Cortes and the Python Spatial Analysis Library (PySAL) team, giving a great contribution to the study of segregation. Eli Knap, one of the co-authors of the paper, has a great blog post summarizing some of the key contributions of the package.

Cortes, R. X., Rey, S., Knaap, E., & Wolf, L. J. (2019). An open-source framework for non-spatial and spatial segregation measures: the PySAL segregation module. Journal of Computational Social Science, 1-32.

Abstract:

In human geography and the urban social sciences, the segregation literature typically engages with five conceptual dimensions along which a given society may be considered segregated: evenness, isolation, clustering, concentration and centralization (all of which can incorporate or omit spatial context). Over the last several decades, dozens of segregation indices have been proposed and studied in the literature, each of which is designed to focus on the nuances of a particular dimension, or correct an oversight in earlier work. Despite their increasing proliferation, however, few of these indices remain used in practice beyond their original conception, due in part to complex formulae and data requirements, particularly for indices that incorporate spatial context. Furthermore, existing segregation software typically fails to provide inferential frameworks for either single-value or comparative hypothesis testing. To fill this gap, we develop an open-source Python package designed as a submodule for the Python Spatial Analysis Library, PySAL. This new module tackles the problem of segregation point estimation for a wide variety of spatial and aspatial segregation indices, while providing a computationally based hypothesis testing framework that relies on simulations under the null hypothesis. We illustrate the use of this new library using tract-level census data in two American cities.

image credit: Cortes et al 2019

Marcadores:

Python,

Segregation

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

What do we know about Transit Oriented Development (TOD)?

Author links open overlay

For those interested in what Transit Oriented Development (TOD) can and cannot do to promote more sustainable and inclusive cities, there are two brand new papers reviwing decades of TOD reseach and policy. These papers should probably be added to that neverending reading pile.

- Jamme, H. T., et al. (2019). A Twenty-Five-Year Biography of the TOD Concept: From Design to Policy, Planning, and Implementation. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(4), 409-428.

- Ibraeva, A. et al. (2020) Transit-oriented development: A review of research achievements and challenges. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 132, 110-130

The TOD of Curitiba, Brazil

credit: Rafael Pereira via Google Maps

Marcadores:

TOD

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

Monday, November 11, 2019

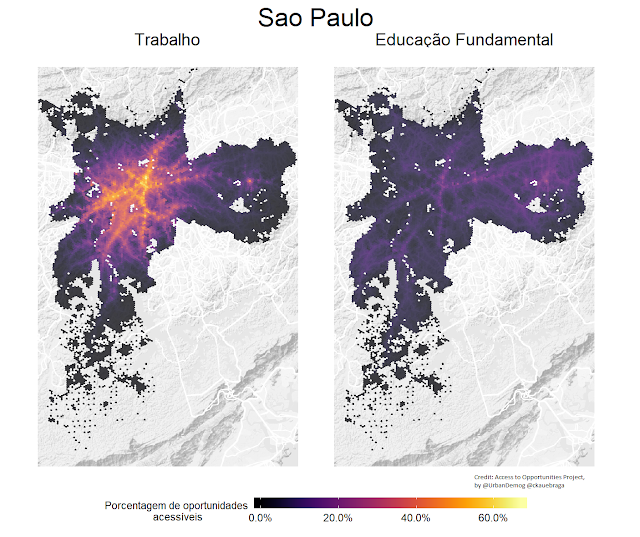

A glimpse into the accessibility landscape of São Paulo

These maps show the proportion of jobs and elementary schools accessible by public transport in under one hour in São Paulo. These are some of the results of the Access to Opportunities Project I'll be presenting this week at the Brazilian Conference on Transport Research ANPET 2019. I hope to see some of you there.

Marcadores:

Access to Opportunities Project

Thursday, November 7, 2019

New paper out: Distributional effects of transport policies on inequalities in access to opportunities

Glad to share our paper on "Distributional effects of transport policies on inequalities in access to opportunities in Rio de Janeiro" is now out the Journal of Transport and Land Use. I summarize the paper findings and contributions in this short thread here, but please feel free to read the full paper. The journal is open access!

Pereira, R. H. M., Banister, D., Schwanen, T., & Wessel, N. (2019). Distributional effects of transport policies on inequalities in access to opportunities in Rio de Janeiro. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 12(1). doi:10.5198/jtlu.2019.1523

Abstract:

The evaluation of social impacts of transport policies has been attracting growing attention in recent years. Yet studies thus far have predominately focused on developed countries and overlooked whether equity assessment of transport projects is sensitive to the modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP). This paper investigates how investments in public transport can reshape socio-spatial inequalities in access to opportunities, and it examines how MAUP can influence the distributional effects of transport project evaluations. The study looks at Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) and the transformations carried out in the city in preparation for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics, which involved substantial expansion in public transport infrastructure followed by cuts in service levels. The paper uses before-and-after comparison of Rio's transport network (2014-2017) and quasi-counterfactual analysis to examine how those policies affect access to schools and jobs for different income groups and whether the results are robust when the data is analyzed at different spatial scales and zoning schemes. Results show that subsequent cuts in service levels have offset the accessibility benefits of transport investments in a way that particularly penalizes the poor, and that those investments alone would still have generated larger accessibility gains for higher-income groups. These findings suggest that, contrary to Brazil’s official discourse of transport legacy, recent policies in Rio have exacerbated rather than reduced socio-spatial inequalities in access to opportunities. The study also shows that MAUP can influence the equity assessment of transport projects, suggesting that this issue should be addressed in future research.

Marcadores:

Accessibility,

Biographical note,

BRT,

Equity,

Justice,

Rio de Janeiro

Wednesday, November 6, 2019

Positive thinking

Induced demand and the Black Hole Theory of Highway Investment

1970: One more lane will fix it.— Urban Planning & Mobility (@urbanthoughts11) November 4, 2019

1980: One more lane will fix it.

1990: One more lane will fix it.

2000: One more lane will fix it.

2010: One more lane will fix it.

2020: ?pic.twitter.com/NjS1IPORG2

via @avelezig

Marcadores:

Congestion,

induced demand

Tuesday, October 29, 2019

City walkability and upward social mobility

Here is a recent paper with some interesting findings suggesting that more walkable cities can facilitate upward social mobility (Thanks Pedro Nery for the pointer). The results are rather consistent with the studies by Raj Chetty and colleagues at Opportunity Insights, but it extends previous research by exploring how walkability can have positive effects on social mobility via both accessibility and psychological channels.

Oishi, S., Koo, M., & Buttrick, N. R. (2018). The Socioecological Psychology of Upward Social Mobility. American Psychologist. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000422

Abstract

Intergenerational upward economic mobility—the opportunity for children from poorer households to pull themselves up the economic ladder in adulthood—is a hallmark of a just society. In the United States, there are large regional differences in upward social mobility. The present research examined why it is easier to get ahead in some cities and harder in others. We identified the “walkability” of a city, how easy it is to get things done without a car, as a key factor in determining the upward social mobility of its residents. We 1st identified the relationship between walkability and upward mobility using tax data from approximately 10 million Americans born between 1980 and 1982. We found that this relationship is linked to both economic and psychological factors. Using data from the American Community Survey from over 3.66 million Americans, we showed that residents of walkable cities are less reliant on car ownership for employment and wages, significantly reducing 1 barrier to upward mobility. Additionally, in 2 studies, including 1 preregistered study (1,827 Americans; 1,466 Koreans), we found that people living in more walkable neighborhoods felt a greater sense of belonging to their communities, which is associated with actual changes in individual social class.

Marcadores:

Accessibility,

social mobility,

walkability

Saturday, October 26, 2019

The urban footprint of the largest urban areas of Brazil

All my procrastination energy led to me to create this nice little image comparing the footprint of the largest urban agglomeration in Brazil. I created this figure using R and geobr, a package that facilitates downloading official geospatial data of Brazil (a quick intro to geobr here). In our latest update, we included official data on the urban footprint of all Brazilian cities in 2005 and 2015.

[click on the image to enlarge]

Marcadores:

Brazil,

cartography,

geobr,

Urbanization

Tuesday, October 22, 2019

Pushing regional studies beyond its borders

New paper hot off the press discussing 5 perspectives to push the bounderies of regional studies. Good read to catch up with the literature and to reflect on potential research projects, specially if you're considering a graduate degree or grant application.

This paper explores how to push the field of regional studies beyond its present institutional, conceptual and methodological borders. It does this from five perspectives: innovation and competitiveness; globalization and urbanization; social and environmental justice; local and regional development; and industrial policy. It argues that the future of regional studies requires approaches that, in combination, result in the pushing on (by creating), pushing off (by consolidating), pushing back (by critiquing) and pushing forward (by collectively constructing) the field.

Marcadores:

regional development

Sunday, October 20, 2019

Tuesday, October 15, 2019

Fully funded PhD scholarship at the Transport Studies Unit at Oxford

Heads up: The Transport Studies Unit (TSU) at the School of Geography and the Environment of the University of Oxford will have one fully funded, three-year Doctor of Philosophy (DPhil/PhD) scholarship available for a citizen from a country in Africa, South and South-East Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean or small island states in the Pacific or Indian Ocean. More details here.

I'm certainly biased here, but this is a great opportunity to study along brilliant researchers in an incredibly vibrant department at one of the top universities in the world. This is a competitive scholarship, sure, but this should not stop you from applying. You only need one spot. ;)

Saturday, October 12, 2019

The Build-up of OpenStreetMap data in East Asia

Another neat dataviz from the ItoWorld team, this time visualizing all the edits to road networks in OpenStreetMap for East Asia since 2008.

OpenStreetMap Series: East Asia Build-up from ItoWorld on Vimeo.

OpenStreetMap Series: East Asia Build-up from ItoWorld on Vimeo.

Marcadores:

dataviz,

OpenStreetMap

Friday, October 11, 2019

How many people have ever lived on Earth?

Have a guess. I can only say I was wrong by a lot :) Now select this back box to see how close your guess was. 109 billion There is a nice article by PRB on this question and how one arrived at this estimate. HT Sergei Soares.

Marcadores:

History,

World Population

Tuesday, October 8, 2019

Precious advice on academic writing

Resubmitting to different journals pic.twitter.com/9cpsPvxG2e— Oded Rechavi 🦉 (@OdedRechavi) October 7, 2019

Marcadores:

Academic writing

Saturday, October 5, 2019

World population projected to reach 10.9 billion by 2100

The UN Population Division published this year its report World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision with lots of goodies, including the latest world population projections. Here are the ten key findings of the report:

- The world’s population continues to increase, but growth rates vary greatly across regions

- Nine countries will make up more than half the projected population growth between now and 2050

- Rapid population growth presents challenges for sustainable development

- In some countries, growth of the working-age population is creating opportunities for economic growth

- Globally, women are having fewer babies, but fertility rates remain high in some parts of the world

- People are living longer, but those in the poorest countries still live 7 years less than the global average

- The world’s population is growing older, with persons over age 65 being the fastest-growing age group

- Falling proportions of working-age people are putting pressure on social protection systems

- A growing number of countries are experiencing a reduction in population size

- Migration has become a major component of population change in some countries

A neat visualization of population growth by region based on UN Population Division (2019) medium variant scenario projections. This chart was put together by Our World in Data, who have plenty more material on this and other topics.

Marcadores:

Projections,

World Population

Friday, September 27, 2019

A list of my favorite entries to the 2019 'Information is Beautiful Awards'

Every year since 2012, David McCandless (founder of Information is Beautiful) and a team analyze hundreds of data visualizations, infographics, interactives etc to recognize some of them with the Information is Beautiful Awards. Here is a list in no particular order of some of my favorite entries to the 2019 Information is Beautiful Awards.

- Racial Disparities In Illinois Traffic Stops

- Britain's Top 40 Most Complex Motorway Junctions

- Imaging The Entire Earth, Every Day

- How much warmer is your city?

- Visualising the world’s addiction to plastic bottles. Every day, 1.3 billion plastic bottles are sold around the world

- Earth At Night, Mountains Of Light, by Jacob Wasilkowski

- The Opportunity Atlas

- American segregation, mapped at day and night

- Dynamic visualization of schedules in The Netherlands

- Visualising TomTom Probe Data In Amsterdam

- How does your zip code impact your health?

- 3D Map of Land Values in Japan: 1989 - 2019

- Britain’s Most Trodden Paths

- The spatial associattion between the prevalence of diabetes in London neighborhoods with the diversity of nutrients of 1.6B grocery purchases

- How Many Years Do We Lose To The Air We Breathe?

- The complex relationship between certainty and scientific discovery

- The Minimum Fleet Network model

Marcadores:

Assorted links,

dataviz

Thursday, September 26, 2019

geobr: data updates

Some of you are already familiar with geobr, an R package that we developed in Ipea to facilitate downloading official spatial data sets of Brazil (a quick intro to geobr here). The stable version 1.0 was published on CRAN a couple of months ago. Since then, we have added some new data sets.

geobr now brings official spatial data of natural biomes, indigenous lands of all ethnicities in Brazil according to stage of demarcation, and risk areas prone to landslides and floods in Brazil. These data sets are currently only available in the development version of the package, wich can be installed with devtools::install_github("ipeaGIT/geobr") .

Wednesday, September 25, 2019

Monday, September 23, 2019

Coloring slavery history in Brazil

Marina Amaral (Twittter) is a renowned digital colorist. Marina has an incredible portfolio, coloring photographs of Marie Curie, Abraham Lincoln, Albert Einstein, tragic moments in the WWII and victims of Auschwitz concentration camp.

In her latest project, Marina is coloring portraits of black people (mostly slaves) taken in 1869 by Arthur Henschel in Brazil. Wonderful work.

credit: Marina Amaral

Thursday, September 19, 2019

Public investment and state sponsored speculation

Great piece with a critical take and neat data analysis of how the New York’s High Line project affected real state property prices. It was written by The Dark Matter Labs & Centre for Spatial Technologies teams, who use this case to draw some interesting reflections on public investment and state sponsored speculation.

credit: Dark Matter Labs & Centre for Spatial Technologies

Marcadores:

Real Estate,

Transport,

urban development

Friday, September 13, 2019

The Access to Opportunities Project, live webinar with preliminary results

This week, on Sept 18 at 7pm (GMT), we will be broadcasting a live webinar to present some of the preliminary results of the Access to Opportunities Project. The webinar will be broadcast in Portuguese on this link and we will also be answering questions about the project.

Here is a quick summary about the project:

Here is a quick summary about the project:

How many jobs can one access in less than an hour using public transport? How long does it take to get to your nearest healthcare facility or school? The answers to these questions are a direct result of the urban and transport policies implemented in our cities. These policies largely determine the ease with which people from different social groups and income levels can access employment opportunities, health and education services. These policies play a key role in building more just and inclusive cities and reducing inequalities in access to opportunities. Although the issue of transport accessibility has been widely studied in cities in the Global North, this topic has received much less attention in the global South and particularly in Brazil.

My team and I at the Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea) are launching the Access to Opportunities Project to map and analyze urban accessibility in Brazilian cities. The purpose of the project is to estimate accessibility to job opportunities, schools and health services by public transport, walking, cycling and driving at high spatial resolution for all of the largest urban areas in the country. This year, the project will include public transport accessibility estimates for 6 major cities (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, Fortaleza, Porto Alegre and Curitiba), as well as walking and cycling accessibility estimates for the 20 largest cities in Brazil. We are planning to expand the project soon to include other urban areas.

The Access to Opportunities Project is carried out in collaboration with the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP - Brazil), and it will bring annual updates on the accessibility landscape of Brazilian cities. One of the expected results of the project is to generate a wealth of data that will be made publicly available to policy makers and researchers, with whom we will be able to collaborate to analzye particular case studies and conduct international comparative research.

Marcadores:

Access to Opportunities Project,

Accessibility,

Brazil,

Ipea

Wednesday, September 11, 2019

Comparing public transport ridership trends in the USA and France

Yonah Freemark (Twitter) is a PhD student at MIT and author of The Transport Politic, probably one of the most widely read websites in the field of transportation research and policy. Yonah has recently published a very great piece looking at the trends of public transport ridership between 2002 and 2018 for the 30 largest urban areas in the USA and France. This is the general outlook:

"Between 2002 and 2010, both countries saw increases in transit use in their major cities. The average U.S. city’s ridership increased by 6 percent over that time (though the peak was in 2008). [...]. This trend has diverged dramatically since the Great Recession, however. While the average French urban region saw its ridership increase by 32 percent between 2010 and 2018, U.S. regions saw ridership decline by 6 percent on average."

The piece is interesting throughout, with a nuanced analysis of what could explain the success and failure of French and American cities in building public transport ridership. Highly recommended.

Marcadores:

ridership

Monday, September 9, 2019

Thursday, September 5, 2019

Wednesday, September 4, 2019

Monday, September 2, 2019

Who wins and who loses from rent control?

Short/simple answer: everyone loses in the long run.

Last year, I shared here a NBER Working Paper by Rebecca Diamond (Stanford) and colleagues on the effects of rent control on tenants, landlords, and inequality. This issue always makes a comeback and since the paper has has now been published on AER, I thought it would be good to post about this study again. Thanks Max Roser and Carlos Goes for the pointers

Diamond, Rebecca, Tim McQuade, and Franklin Qian. 2019. The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco. American Economic Review, 109 (9): 3365-94. [ungated version of the paper]

Using a 1994 law change, we exploit quasi-experimental variation in the assignment of rent control in San Francisco to study its impacts on tenants and landlords. Leveraging new data tracking individuals' migration, we find rent control limits renters' mobility by 20 percent and lowers displacement from San Francisco. Landlords treated by rent control reduce rental housing supplies by 15 percent by selling to owner-occupants and redeveloping buildings. Thus, while rent control prevents displacement of incumbent renters in the short run, the lost rental housing supply likely drove up market rents in the long run, ultimately undermining the goals of the law.

Marcadores:

Housing

Wednesday, August 28, 2019

Tuesday, August 27, 2019

My interview for the Caos Planejado podcast

Today is the 5th anniversary of Caos Planejado, a great Brazilian blog focused on urban planning, economics and innovation. Long live! Anthony Ling (the head of Caos Planejado) interviewed me for their podcast a few months ago, when we talked about my PhD research, my ongoing work on the Access to Opportunities Project and other topics related to innovation, data and equity in urban mobility. The interview was recorded in Portuguese and you can listen to it here.

Marcadores:

Accessibility,

Equity,

interview,

Mega‐events,

podcast,

thesis

Monday, August 19, 2019

The influence of ride-hailing on users' travel behavior

New paper hot off the press, by Alejandro Tirachini (Twitter).

Tirachini, A., & del Río, M. (2019). Ride-hailing in Santiago de Chile: users’ characterisation and effects on travel behaviour. Transport Policy. Volume 82, October 2019, Pages 46-57

Abstract:

Tirachini, A., & del Río, M. (2019). Ride-hailing in Santiago de Chile: users’ characterisation and effects on travel behaviour. Transport Policy. Volume 82, October 2019, Pages 46-57

Abstract:

In this paper, an in-depth examination of the use of ride-hailing (ridesourcing) in Santiago de Chile is presented based on data from an intercept survey implemented across the city in 2017. First, a sociodemographic analysis of ride-hailing users, usage habits, and trip characteristics is introduced, including a discussion of the substitution and complementarity of ride-hailing with existing public transport. It is found that (i) ride-hailing is mostly used for occasional trips, (ii) the modes most substituted by ride-hailing are public transport and traditional taxis, and (iii) for every ride-hailing rider that combines with public transport, there are 11 riders that substitute public transport. Generalised ordinal logit models are estimated; these show that (iv) the probability of sharing a (non-pooled) ride-hailing trip decreases with the household income of riders and increases for leisure trips, and that (v) the monthly frequency of ride-hailing use is larger among more affluent and younger travellers. Car availability is not statistically significant to explain the frequency of ride-hailing use when age and income are controlled; this result differs from previous ride-hailing studies. We position our findings in this extant literature and discuss the policy implications of our results to the regulation of ride-hailing services in Chile.

Marcadores:

Ride-hailing,

Uber

Monday, August 12, 2019

geobr: easy access to official spatial data sets of Brazil

I'm glad to annouce that geobr is now officially available on CRAN. Here and here are quick intros on how to use geobr to get easy and quick access to shape files and other official spatial data sets of Brazil. The package currently includes several data sets for various years such as states, regions, municipalities, census tracts, statistical grid and others. The github repository is this, in case you want to keep track of the latest developments.

The package was developed by my team and I at the Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea). We are constantly working to expand and improve the package, so if you have any suggestions/contributions, please feel free to open an issue on Github.

Wednesday, July 31, 2019

Friday, July 26, 2019

Climate change and the glass half full

Quote of the day:

"Some people complain that this is the hottest summer in the last 125 years, but I like to think of it as the coolest summer of the next 125 years! Glass half full!" (Carter Bays)

Marcadores:

climate change,

Quote

Thursday, July 25, 2019

A spatial database of health facilities in sub Saharan Africa

Interesting new paper analyzing accessibility to emergency hospital care in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015. The authors have done a laborious work to map public health facilities and the data is openly available here. HT Moritz Kraemer.

Interesting new paper analyzing accessibility to emergency hospital care in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015. The authors have done a laborious work to map public health facilities and the data is openly available here. HT Moritz Kraemer.

Ouma, P. O., et al. (2018). Access to emergency hospital care provided by the public sector in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015: a geocoded inventory and spatial analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 6(3), e342-e350.

Abstract:

BackgroundTimely access to emergency care can substantially reduce mortality. International benchmarks for access to emergency hospital care have been established to guide ambitions for universal health care by 2030. However, no Pan-African database of where hospitals are located exists; therefore, we aimed to complete a geocoded inventory of hospital services in Africa in relation to how populations might access these services in 2015, with focus on women of child bearing age.MethodsWe assembled a geocoded inventory of public hospitals across 48 countries and islands of sub-Saharan Africa, including Zanzibar, using data from various sources. We only included public hospitals with emergency services that were managed by governments at national or local levels and faith-based or non-governmental organisations. For hospital listings without geographical coordinates, we geocoded each facility using Microsoft Encarta (version 2009), Google Earth (version 7.3), Geonames, Fallingrain, OpenStreetMap, and other national digital gazetteers. We obtained estimates for total population and women of child bearing age (15–49 years) at a 1 km2 spatial resolution from the WorldPop database for 2015. Additionally, we assembled road network data from Google Map Maker Project and OpenStreetMap using ArcMap (version 10.5). We then combined the road network and the population locations to form a travel impedance surface. Subsequently, we formulated a cost distance algorithm based on the location of public hospitals and the travel impedance surface in AccessMod (version 5) to compute the proportion of populations living within a combined walking and motorised travel time of 2 h to emergency hospital services.FindingsWe consulted 100 databases from 48 sub-Saharan countries and islands, including Zanzibar, and identified 4908 public hospitals. 2701 hospitals had either full or partial information about their geographical coordinates. We estimated that 287 282 013 (29·0%) people and 64 495 526 (28·2%) women of child bearing age are located more than 2-h travel time from the nearest hospital. Marked differences were observed within and between countries, ranging from less than 25% of the population within 2-h travel time of a public hospital in South Sudan to more than 90% in Nigeria, Kenya, Cape Verde, Swaziland, South Africa, Burundi, Comoros, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Zanzibar. Only 16 countries reached the international benchmark of more than 80% of their populations living within a 2-h travel time of the nearest hospital.InterpretationPhysical access to emergency hospital care provided by the public sector in Africa remains poor and varies substantially within and between countries. Innovative targeting of emergency care services is necessary to reduce these inequities. This study provides the first spatial census of public hospital services in Africa.

Marcadores:

Accessibility,

Africa,

database,

Health

Wednesday, July 10, 2019

Off to the UK

I'm off to the UK to participate in my graduation ceremony at Oxford and to celebrate my partner's graduation at Cambridge the other place. Really excited because both our parents will be there to celebrate with us. Yep, this will require some serious diplomatic skills, though :)

My graduation will happen this Saturday, on July 13th between 11am and 12pm. So, you will be able to see a bunch of academics weirdly dressed wondering around Oxford at 12pm on that day. You can actually see this through the live webcam of the Oxford Martin School in case you really need something to procrastinate with.

ps. Blog activity will be low over the next couple of weeks but you'll probably see me Tweeting regularly while I'm queuing for something somewhere in England.

Marcadores:

Biographical note

Tuesday, July 9, 2019

We're hiring research assistants to work with Spatial Data Science at Ipea

A few readers might be interested in this post. We are hiring 4 research assistants to work with (spatial) data science on urban, regional and environmental research and policies at the Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea), in Brasília. Great team with lots of computational resources, rich data sets and plenty of challenging data analyses to improve public policies.

Sunday, July 7, 2019

Music for the weekend

Soundtrack for a weekend of good bye to João Gilberto, one of the fathers of Bossa Nova. A Brazilian giant.

Thursday, July 4, 2019

The winners and losers of the transport legacy of megaevents

Summarizing the core elements of one's research to communicate with a wide audience is among the most challenging and yet important aspects of what researchers do. Here's my best attempt so far to summarize my PhD research to a broad audience, published in my favorite online newspaper Nexo. The text is in Portuguese.

Marcadores:

Accessibility,

Biographical note,

Equity,

Mega‐events,

Rio de Janeiro

Monday, July 1, 2019

geobr: shapefiles and official spatial data sets of Brazil in R

In 2012, I published here a blog post about where to find shapefiles of Brazil. Since then, this has become one of the most popular posts in 9 years of the blog. However, the links to the original data sets change every now and then, and it gets a bit tricky to find the most up to date data. My team and I at the Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea) have created geobr, an R package that allows users to easily access shapefiles of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) and other official spatial data sets of Brazil.

The geobr package currently includes a variety of data sets, such as the shapefiles of municipalities and states (from 1872 to 2018), census weighting areas, a spatial grid with population count at a resolution of 200 x 200 meters, a geolocated database of health facilities in the country etc. All the data sets are read into R as sf data. We will gradually add other databases to the package, but feel free to make specific requests and suggestions by opening new issues on the GitHub page of geobr or tweeting the hashtag #geobr.

The advantage of geobr: Intuitive syntax that provides easy and quick access to a wide variety shapefiles and official spatial data sets with updated geometries for various years using harmonazied attributes and geographic projections across geographies and years.

Sunday, June 30, 2019

Interactive visualization of large-scale spatial data sets in R

In the beginning, there were only static maps. Over the past years we have seen the creation of new packages like mapview and mapedit that allow one to interactively visualize and edit spatial data in R. Despite these developments, it was still a bit tricky to visualize large spatial data sets in R. Not anymore.

Two packages that are pushing our capabilities to interactively visualize large-scale spatial data sets in R:

Hats off to these two!

- leafgl, by Tim Salabim (the main person behind mapview and mapedit)

- mapdeck, by David Cooley from Symbolix (who is also behind googleway and spatialwidget)

Hats off to these two!

leafgl

Marcadores:

big data,

Interactive dataviz,

R

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

9th Anniversary of Urban Demographics !

Today is the 9th Anniversary of Urban Demographics. I must say the blog has never been as quiet as in the past year. This is due to various reasons. I focused a lot of my time over the past year in finishing my PhD, getting back to work on project/paper collaborations that had been on hold for a long time and perhaps I spent too much time travelling. Sorry, family. Sorry, planet. Personally and professionally, though, it has been an incredible year. I've finally became a doctor (1st in the family, Mom was very proud), I received awards from the AAG and the ITF/OECD, got a few studies published, I've met a bunch of incredible people, and started a few new projects that I'm very excited about and which I'll be sharing here in due time.

Nowadays, I spend less time procrastinating working on the blog than on Twitter, which I find an increasingly rich source of dog pictures information and interaction with other researchers. In the end, the blog has been a bit quite but I still find it incredibly useful to share interesting studies, data, links etc. By the stats of the blog, I'm glad to see a few people still find it useful too. Here are just some quick stats that show a summary of the blog over the past year.

- 84 posts, an average of ~1.6 posts per week

- 20,948 visits, an average of ~57 visits per day (large drop from previous year)

- 9,175 followers on Twitter

- 3,188 likes/followers on Facebook

- 725 RSS feed subscribers

- Assorted R Packages for Spatial Analysis

- 3D interactive map of population densities across the globe

- Mapping the diversity of population ageing across Europe with a ternary colour scheme

- Visualizing transport mode share using a ternary colour scheme

- Travel time to closest healthcare facility in Rio de Janeiro

and 10 of my favorite posts:

- The geography of Manhattan distorted by travel-times

- Racial inequity in who pollutes and who gets exposed to pollution

- Creating a simple world map of cities in R

- A 195 gigapixel Urban Picture of Shanghai

- The race for the largest city in the world over the past 500 years

- Why you should probably share your preprints

- How complete is OpenStreetMap data coverage?

- Using GIFs to explain what various causal inference methods

Where do readers come from? (140 countries | 2,598 Cities)

- United States (32.3%)

- Brazil (13%)

- United Kingdom (6.3%)

- Australia (3.5%)

- Canada (3.4%)

Marcadores:

Blogs

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)